Conducting library searches is the art of being just specific enough using a simple set of tools. This guide will introduce you to the basic terms, functions, and limitations of the DTL’s system, and give you some tools to begin creating better searches. It is long, with a lot of explanation and examples. Not everyone may want or need this level of detail. If you just want to get started or need a refresher, here is a great, short guide to Boolean searches from the MIT libraries. Very basic instructions for using the catalog and logging in to access materials are available here. Instructions for getting access to materials that the DTL doesn’t own are here.

Why This Guide?

The DTL, like most library systems and the databases they subscribe to, does not function like an internet browser search. Google and other browsers use complex algorithms to analyze the words you typed into the field and determine synonyms and related topics, sometimes making connections to your own internet history. The results you get when the page finishes loading may or may not include the exact words you typed. The search might find perfect matches that you didn’t know to search for, and they might limit your results based on factors they don’t tell you they’re using, like your location or browsing history. You can even phrase your Google search as a question, and the algorithms will often recognize the syntax and return results that answer the question.

The DTL doesn’t have these capabilities. It can give limited autofill suggestions in the search bar, but otherwise it reads exactly what you typed and searches the available records in specific ways. The last section of this guide gives some of the technical details to help you understand why, but for the most part this guide is going to focus simply on the how.

Basic Boolean Operators

Library catalogs use Boolean logic to read your searches and deliver lists of results. Boolean logic is a basic system of true/false logic based on the work of mathematician George Boole. It is founded on the three operators AND, OR, and NOT. Most computer programming languages have a way of expressing and reading these operators, and they have been a foundational part of digital library searches for decades.

This guide will use italics to indicate search terms, because quotation marks and some other punctuation, as you’ll see, have specific meanings that will change your search. To avoid confusion, titles of works and words with emphasis will be underlined. You do not need to use italics when you search the DTL. Similarly, this guide will put the three basic Boolean operators in all caps, as they are in the paragraph above this one, so they’re easy to see and identify as operators. The library system is not case-sensitive. You can type the operators in all caps if that helps you, but it won’t make a difference to the system. You will also see that throughout this guide, proper names in search phrases may or may not be capitalized. The system will not read a difference between rogers and Rogers.

The most common and the default operator is AND. When you type a multi-word phrase into the search bar, like process theology, the system reads process AND theology. It will search for any record that contains both the words process and theology anywhere in the record, but it will not make a difference if or how those words are used together. So a book titled Process Theology as Political Theology shows up in the same list of results as a book called Intercultural Theology with the generic word “process” somewhere in the description.

That doesn’t mean this most basic method of searching doesn’t work. Since “process theology” is a technical term and there are a lot of books and papers in the DTL about it, if you just search for the phrase process theology you’ll find a lot of helpful materials. In fact, if you just type process, you get the journal Process Studies in the first page of results. You also get a lot of irrelevant stuff, though, so if you find yourself wading through a lot of unhelpful results, you may need to redesign the way you’re phrasing your search.

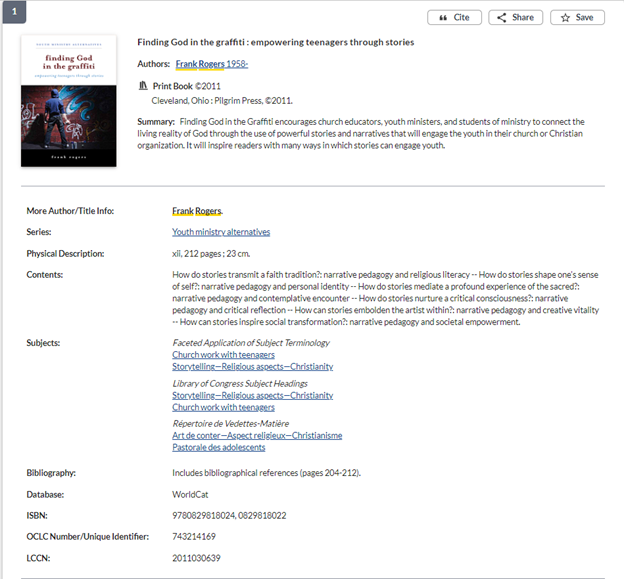

Adding more words will naturally narrow down your search. If there are 10,000 records with both process and theology somewhere in them, adding philosophy will eliminate any of those 10,000 without that third word. The more words you add to a basic search like this, the more targeted and therefore more limited it will be. Most of the time you can find a specific book or article simply by typing in the author’s last name and two or three important words from the title. Go to the DTL and search for the phrase rogers god graffiti. You should get CST Professor Frank Rogers’s book Finding God in the Graffiti as the first or second result.

- Tip: Sometimes as you’re typing the system will give you a dropdown list of potential search terms. You can select one of those terms if it matches what you’re looking for, or you can ignore the list and do it on your own. If you decide to ignore the dropdown list, you may need to manually click the search button on the right side of the search bar, because sometimes the top item in the dropdown list will automatically select, so if you just hit the return key to search it will search for that instead of what you typed. Every computer system has its minor annoying features, and this is one of the DTL catalog’s.

A useful way to change up your search phrasing is the operator OR. This operator is most helpful when you’re working with synonyms. The search process OR theology will find every record with the word process and every record with the word theology, including records with both of them. That’s probably way too much, and most of them will be unrelated. But maybe you’re looking for materials on Protestant religious professionals. You can type pastor OR minister to get a wider range of results than if you just searched for one of the words by itself. This phrasing accounts for the fact that there are multiple and sometimes interchangeable ways to refer to someone who leads a Protestant church, and you can’t be sure which one a useful book or article might use.

Since OR is likely to find much larger numbers of results than AND, it’s best to use it carefully or in combination with other operators.

This is the most challenging operator, because it’s easy to accidentally eliminate things you might want to see. It’s best to use NOT when you’re searching for a term that has uses in multiple very different contexts or if you want to eliminate items on an obscure subtopic.

Let’s say you want to do research on Christmas, but you aren’t interested in materials about Santa Claus. You can search for Christmas NOT Santa, (the section below on quotation marks will explain how to get the whole name Santa Claus into this search), but that might mean you don’t see records for books that would mostly be useful but happen to have an easily skippable chapter on Santa Claus. This might not be a good time to use NOT.

However, NOT can be useful in other cases. Maybe you type Christmas into the catalog and get millions of results, but for some reason a lot of the top results are materials about the plant sometimes called the Christmas cactus. In this case you can try Christmas NOT cactus or Christmas NOT botany or something similar to eliminate those irrelevant results. The DTL has access to a lot of medical journals because they come bundled with some other subscriptions, so you may find yourself in situations when adding NOT medicine or similar can help declutter your results.

You can also use NOT to keep more obscure subtopics out of your results. Santa Claus is a highly integrated feature of Christmas in the United States, so using NOT to avoid materials about Santa might backfire. However, the European figure Krampus has only recently gained a lot of visibility in the US, so if you’re not interested in German and Austrian celebrations of Christmas, maybe the phrase Christmas NOT Krampus will help you narrow your search down.

- Tip: It is usually more effective to add an AND to your search rather than a NOT. Alexandria AND Egypt will get you more relevant results than Alexandria NOT Virginia, both because it positively identifies your target, and because you won’t accidentally eliminate books about the Egyptian city that happened to be written by scholars named Virginia.

- Tip: NOT phrases are order dependent, meaning Christmas NOT Santa is a different search from Santa NOT Christmas. See the section below on parentheses for more about syntax and order in search strings.

Punctuation and Combining Operators

AND, OR, and NOT are the basic building blocks of a library search, but with a few more symbols and an understanding of operator syntax, you can fine-tune your searches to get the most out of the library.

After the three basic operators, quotation marks are the next most useful feature of library search syntax. Remember how the search process theology really means process AND theology in the system’s language? Quotation marks will tell the system to read “process theology” as a complete phrase, instead. Now instead of finding every record with both of those words somewhere in the record, it will only find records where those words appear together in that exact configuration. This can be helpful if you’re looking for a very specific technical term that is made up of more generic words (like, indeed, process theology), or you can use it to look up specific works by their titles. In the Christmas NOT Santa example above, you could use quotation marks to search Christmas NOT “Santa Claus” if it were important to get the whole name in.

Asterisks (that little star that you can use by hitting the shift and 8 keys together on a standard English language keyboard) are very useful for searching for topics where a root word might come with multiple possible endings.

Instead of doing separate searches for the words theology, theological, theologize, and theologian to make sure you get everything you need, you can simply search for theolog*, and the system will search for the typed letters with any ending. As you can imagine, this is more useful with some roots than with others. For most people, the example of theolog* is probably actually much too broad. Similarly, the search Christ* will get you results with Christ, Christian, Christianity, and Christmas, as well as Christopher, Christchurch, christendom, Christina, christen, and on and on. Make sure to type as much of the word as you possibly can without excluding the endings you want to see (theolog* instead of theo* or, worse, the*). With a few exceptions, roots less than four or five letters probably won’t be helpful.

Asterisks are most useful where you don’t want to differentiate between singular and plural, or where a root might have equally relevant forms in different parts of speech (a noun, verb, adjective, etc., such as Jew and Jewish or oblige and obligation). Adding another operator can help limit the search if there are too many results. For example, the endless possibilities of the term christ* might be narrowed down a very little bit with christ* AND england or christ* AND scripture.

Parentheses enable you to combine multiple operators and determine the order in which they’re read. The system will perform the segment of the string inside in the innermost parentheses first, and then will use the results of that operation to perform the next one.

If you type the phrase with different operators, the system will read the AND operation first. In the string pastor AND Methodist OR Presbyterian, the system will give you all the results that combine the words pastor and Methodist, plus all the results with Presbyterian, whether or not the word pastor is present. If you put AND pastor on the other side of Presbyterian it will still read the AND first. You’d get a lot of things about Presbyterian pastors plus a lot of things about Methodists.

But that probably isn’t what you meant. Instead, use the string pastor AND (Methodist OR Presbyterian). The system will first find all of the records containing either of the words Methodist and Presbyterian, then will narrow the results by selecting the records that also contain the word pastor. You can create even more steps by nesting the parentheses: education AND (pastor AND (Methodist OR Presbyterian)) might be a roundabout way to look for research on denominational seminaries. Make sure to count your parentheses and close all of your phrases.

You can also use parentheses to search for terms that have important synonyms, and you can use multiple separate parenthetical phrases in the same string, like (bible OR scripture) AND (Hebrew OR Jewish).

- Tip: You can create strings as long and as nested as you want, although if your searches are getting very complicated there’s probably an easier way. Try finding different search terms, such as seminary AND (Methodist OR Presbyterian) or seminar* AND denomination* instead of education AND (pastor AND (Methodist OR Presbyterian)) or, if you’re getting very, very specific, head to Google to find the title of the individual book you’re looking for.

- Tip: You don’t need parentheses if you’re using the same operator throughout your string or if you have only one operator. Methodist AND Presbyterian AND Baptist is the same as if you put parentheses anywhere in that string. You only need parentheses when you’re mixing AND, OR, and NOT.

- Tip: It doesn’t matter what order you put things in if you’re using parentheses correctly. (Methodist OR Presbyterian) AND pastor should find the same results as the example above. You could also switch the order of Methodist and Presbyterian.

To increase efficiency, the system will ignore some words, called stop words. Inclusion of these words as part of the search string would return most or even literally all of the records available.

The most common stop words are:

- articles (a, an, the)

- most small prepositions (in, out, of, by, to, on, etc.)

- the verb be and many of its conjugations (are, is, etc.)

- subordinating conjunctions (if, which, that, etc.)

Sometimes it’s easier to type what’s in your head or what you’re used to typing, rather than take the time to sort through all of the things that are irrelevant, even if the parsed version is simpler. The searches bible and the Bible will get you the same results, so there’s no harm in including stop words or capital letters if it would take more effort to stop yourself from typing them. The important thing to remember is that the system doesn’t understand normal English, so including stop words won’t improve your results. The phrase law in the bible is identical, as far as the system is concerned, to law AND bible. If you want to distinguish Deuteronomistic legal codes from modern laws about or based on the Bible, you need to construct a search using distinct terms, such as torah or “deuteronomistic code”.

Of course, stop words and the operators AND, OR, and NOT are normal words that often appear in titles. If you’re looking for a specific work, this is easy to get around in two ways:

- You can choose distinctive words from the title, such as god graffiti or finding god graffiti (including the author’s name for good measure, if you want).

- You can use quotation marks, as in “finding god in the graffiti”.

If the title doesn’t contain any especially distinctive words and you need to include a stop word or an operator word to find it (for example, the book Jesus Christ is not God), quotation marks are the best solution.

Tip: It is very difficult to find full lists of stop words. The ones listed above are safe to assume, but longer prepositions like above, through, or along may or may not be excluded from your searches. Trial and error is a good strategy, and when in doubt, quotation marks will always make sure those words are included. You can even put quotation marks around a single word.

An easy and usually reliable way to search for a resource you already know about is to search for the author’s name plus two or three major words from the title. Above, we tried the example rogers god graffiti. This works nearly all the time, if the title and the author’s name are distinct enough.

But what if they aren’t distinct (a frequent problem in biblical studies, where it’s common to find dozens of books with titles like The Gospel of Matthew or Deuteronomy)? Or what if you remember the book’s title, but without the author’s name you aren’t getting the correct results? Or what if you simply want to see all of the available works by a specific author?

Enter the index identifiers. All of the searches so far in this guide have been keyword searches, which means that they do not specify a particular part of the record to search, and therefore search the entire record. But catalog records are divided into distinct sections. These are explained a little more fully in the section of this guide called Technical Stuff, but for now you just need to know that they exist and you can specify them in your searches.

The most common index identifiers are:

- au = author (In the DTL this will also find editors, translators, other creators and sometimes contributors.)

- ti = title

- su = subject (This searches specific sections of the catalog record, and will not necessarily find all items that could be considered to belong to that subject. See the Technical Stuff section for more.)

To use these identifiers, type them with a colon (:) or equal sign (=) before the search term. You can also use them with other operators, quotation marks, and parentheses, and all of the usual rules apply. Here are a few different ways to find Dr. Rogers’s book:

- ti: “finding god in the graffiti”

- au: Frank Rogers

- au: “Frank Rogers”

- graffiti AND au: rogers

You can also search for an author’s works by finding one of them through a keyword or title search and then clicking on the author’s name where it appears as a link in the record.

- Tip: Although it appears in one of the examples, it’s usually best not to search for an author’s name in quotation marks. This is because not all authors are identified in the system by simply their first and last name. Many authors use initials, shortened names, or middle names, which don’t always appear in the same ways on all of their publications. Some people, often women, may have published under two or three names at different times in their careers, and some authors with Asian or African names adopt Western names that may appear differently in different publications. Librarians have ways of collecting all of these names under a single author record, but the record name might not be the one you’re expecting. Quotation marks may be helpful to distinguish two authors with similar names, but only if you’re sure of the record name.

Behind the Scenes

This section is for people who want to do deep searches, such as finding all or nearly all of the available literature on a topic. It includes a basic description of the technical structures underlying the operations that this guide has already discussed. This provides context for why the catalog works the way it does, which will be helpful as you try to get the most out of it.

Each item in a library catalog has a unique record created using a database cataloging format called machine readable cataloging (MARC). A MARC record consists of many fields whose contents are determined by numbers. For example, field 100 indicates the primary author of a work, and field 245 indicates the title. You won’t see these fields directly, but you can manipulate your searches to make use of them.

Here is a typical DTL catalog record for a book:

The place of everything in this record is determined by MARC fields. There are many possible fields, so you may see different categories for different types of items. For example, records for journal articles will not usually include the “Series” category or the publication location that’s near the top. There are also a lot of fields that you aren’t seeing but that the system can still read. When you use the checkboxes to narrow your search on the left side of the results page (not shown in this image), you’re asking the system to read various fields, such as those for date or language, to make exclusions from the list it has already given you.

There are two quirks that an advanced researcher should know about:

- Although editors and translators are designated by different MARC fields than authors, for convenience all creators will usually appear in the “Author” category in the record, sometimes–but not always–with their actual designation in parentheses after their name. This is important for your citations. Do not rely on the categories as presented in the catalog for accurate citation information. Make sure to look at the item itself to make sure you’re listing authors, editors, translators, publishers, etc., correctly in your footnotes and bibliographies. It is common to find organizations listed in the catalog on the “Author” line, often for things like conference proceedings where the organization simply convened the conference or funded the work, and shouldn’t be cited as a creator.

- The links in the “Subjects” category are pre-determined headings related to specific MARC fields. They will come up in a general keyword search, but if you click one of the links it will only look for other items with that specific heading designated in a MARC field. That means it will not necessarily find every item associated with that topic, since a librarian or technician had to deliberately choose to include it in the record. Subject headings can be very helpful for browsing and for focusing your searches if you’re getting a lot of irrelevant results, but don’t mistake them for exhaustive lists of everything published on a particular topic. The fact that subject headings are pre-determined makes them poor options for starting your search, because you need to know what the subject heading is called before you can search for it. Further, the way they’re phrased is not always intuitive to specialists in a field, especially if vocabulary or other considerations about the topic have changed since the headings were created. It took years of advocacy by librarians to get the subject heading Illegal aliens changed, and then many libraries had to manually update their records to reflect the change. You can browse the very, very extensive full list of Library of Congress subject headings here (but you can see in the record above that other lists exist, often created by the national libraries of other countries): https://www.loc.gov/aba/publications/FreeLCSH/freelcsh.html